Author John Mark O’Leary MRCVS is assistant professor at the UCD Veterinary Teaching Hospital in Dublin, Ireland. He is a specialist in endodontic dentistry treatment for horses and is inviting readers to be involved in his PhD research – see more details below...

Tooth infections in horses that involve the internal living part of the equine tooth – the pulp – can cause pain or discomfort leading to reluctance to drink or eat in some cases, or evasive ridden behaviour. But signs can also be extremely subtle with only minor changes in eating, biting and general demeanour being seen.

Why do horses get tooth infections?

Unlike humans, whose very common cases of tooth decay and associated infections are linked to diet, tooth fractures are a more common cause of pulp damage and inflammation in horses’ teeth.

In a horse’s front teeth (the incisors) problems are most commonly linked to a broken tooth, often associated with a history of a fall on the road.

A horse with broken front teeth. Credit: TI Media

Horses that crib bite may wear down their front teeth faster than they naturally grow – resulting in exposure of the sensitive pulp. Once the pulp is exposed, it will become contaminated with food material and bacteria from the mouth, which leads to infection.

In addition to broken teeth, the other most common cause of inflammation in the pulp of the equine cheek teeth (the molars) is a local bacterial infection that spreads through the natural openings at the tip of the tooth’s root deep inside the gum (the apical foramina) without any changes to the outer surface or crown of the tooth. This is more common in horses under six years old.

Other causes include over-rasping or over-drilling with motorised dental drills and equipment.

How can I tell if my horse has a front tooth infection?

If a horse’s front teeth are affected they may show a reluctance to drink cold water or take hay from a haynet, or evasive ridden behaviour. Horses suffering an acute case typically will resent the exposed pulp being probed with dental equipment, which results in active bleeding.

However, once the infection becomes established, often with food filling the cavity leading to the death of the pulp and the loss of nerve supply (pulpar necrosis and denervation), then there may be no obvious behavioural signs or evasive reactions to probing.

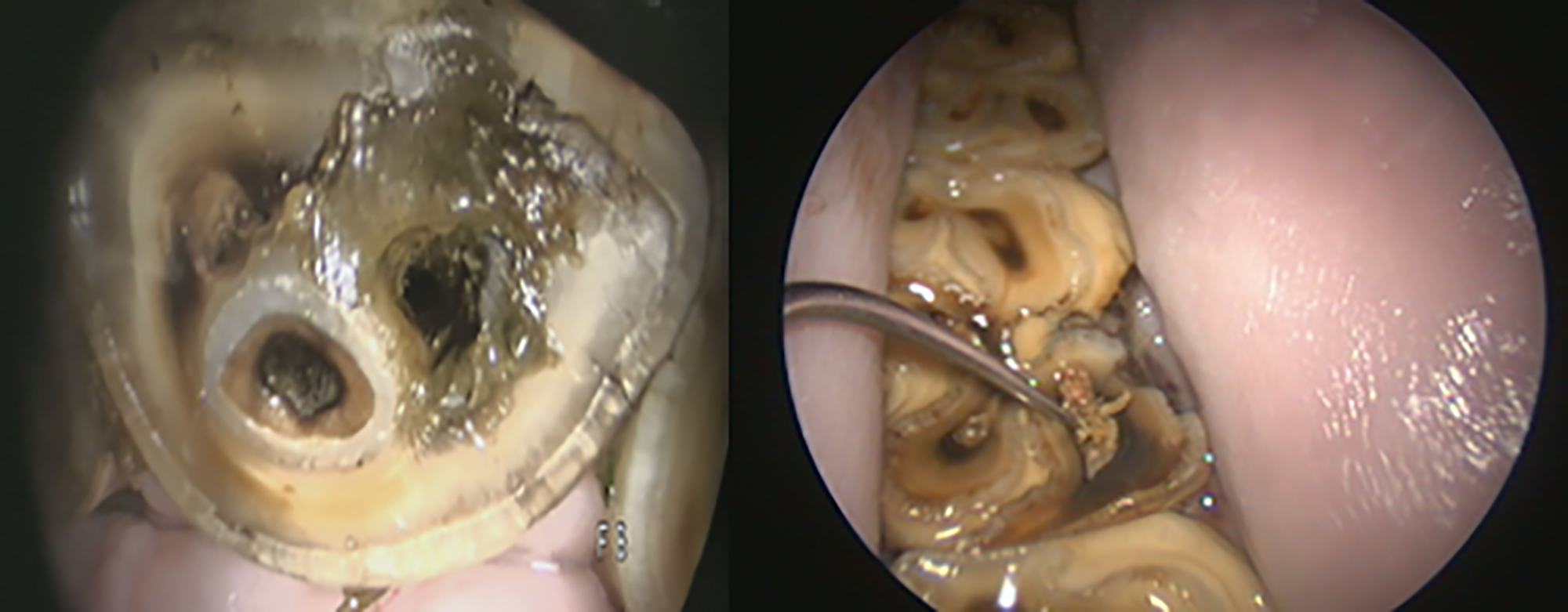

Dentine defects on the surface of an incisor and lower mandibular cheek tooth with associated food contamination and chronic endodontic infections. Credit: John Mark O’Leary MRCVS

The infection can eventually extend through the natural openings at the tip of the tooth’s root (apical foramina) to invade the the tissues around the tooth (periodontium). At this stage, gum recession or draining infected tracts may develop.

How can I tell if my horse has a cheek tooth infection?

Acute infections involving the horse’s cheek teeth typically show little to no obvious signs, unless a displaced fragment of tooth is causing damage to the soft tissue inside the mouth. Recent behavioural studies have reported subtle changes in eating, biting and general demeanour associated with infections in the cheek teeth.

When an established pulp infection reaches the top of the last four upper cheek teeth, bacteria can move into the sinus chambers above, leading to a discharge of pus from the nostril on that side of the face.

Chronic infections reaching into the roots of the other cheek teeth can show up as bony swellings on the face, with or without pus from the draining tracts.

Cases with obvious surface defects on the tooth are often spotted during routine dental examinations. Determining the extent and severity of an infection may require referral to an equine veterinary dentistry specialist.

The specialist will typically undertake a detailed oral examination with a camera and assess the reserve crown and roots using diagnostic imaging. Where X-rays are unable to clearly identify the issue, a more sensitive imaging modality, typically computed tomography (CT) at a hospital centre, may be necessary.

How are tooth infections in horses treated?

Endodontics is the name for the specialised branch of dentistry that treats infections involving pulp of the tooth.

There are three treatment options:

● Vital pulp treatment (VPT), in which all or part of the dental pulp is preserved

● Root canal treatment (RCT) where the pulp is completely removed to the end of the root

● Extraction, where the entire tooth is removed.

Endodontic treatment for horses

The extent and severity of the infection within the pulp and around the root tip (apical) will determine if either VPT or RCT are feasible. Treatment is usually carried out in a standing sedated horse with local anaesthesia.

The four typical steps of endodontic treatment are:

● access with motorised dental drills, typically through the overlying dentine defect on the occlusal surface;

● removal of dead, damaged or infected tissue (debridement) with dental root canal files and disinfecting the endodontic system;

● topical application of a dentine-stimulating product to the remaining viable pulp tissue, and

● finally applying an airtight seal (in the form of a filling) within the cavity created with a material that will wear down at the same rate as the tooth

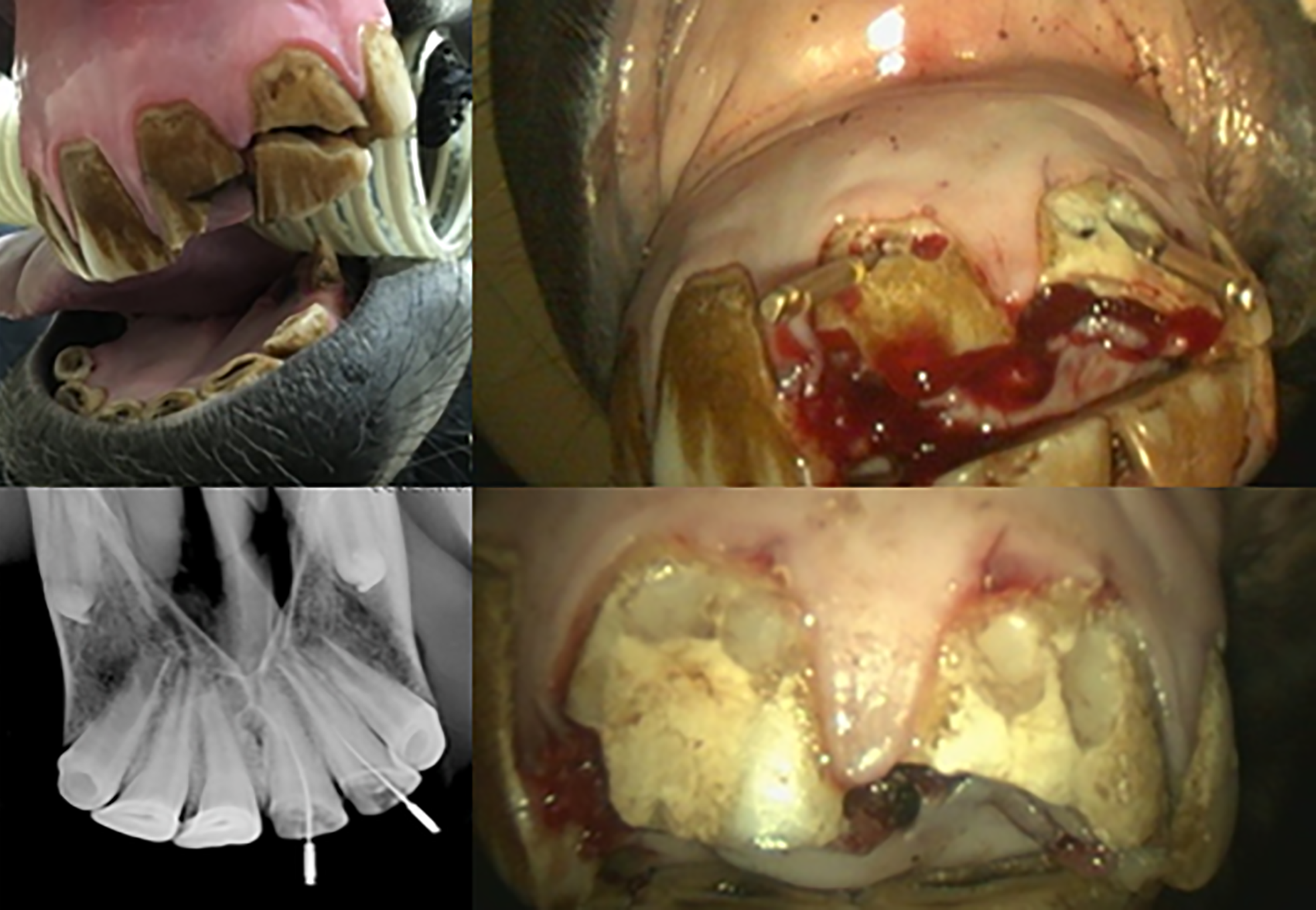

Top left: an acute fracture of upper central and lateral incisor teeth with pulp exposure. Top right: direct endodontic access to the pulp horns at the gum margin. Bottom left: X-ray guidance of debridement depth with dental files. Bottom right: the remaining vital pulp was medicated and the access cavity sealed with a resin composite cement. Credit: John Mark O’Leary MRCVS

Where suitable, VPT is typically the preferred treatment procedure in acute cases. This is because it optimises the potential for return to normal pulp function; it creates a hard dentinal bridge that protects the remaining pulp and preserves blood supply, innervation and immune functions. VPT also avoids having to negotiate the complex root canal system.

RCT is used for more severe and chronic tooth infections. It involves removal of the entire pulp and disinfecting down to the level of the natural openings at the tip of the tooth’s root inside the gum (the apical foramina). This is followed by the application of dentine-stimulating medication at the root level. The remainder of the cavity is sealed to the top of the tooth (the occlusal level).

Often a diseased cheek tooth is still partially healthy and only some of the pulp needs to be accessed and treated. In such a case the inside of the tooth is now unreactive, but the tissues that surround and support the teeth (periodontium) remain healthy and the tooth should erupt normally and remain functional for chewing. However, the lack of complete vitality does predispose the tooth to subsequent development of cavities and fractures.

Extracting horses’ teeth

Extraction is typically chosen for established infections extending to the tissues that surround and support the teeth or previously failed endodontic treatments, but it’s not risk-free.

Frequent long-term conditions following a cheek tooth extraction are the overgrowth of opposing teeth and drifting of adjacent cheek teeth, with increased risks for food entrapment and subsequent inflammation of the tissue surrounding the tooth (periodontitis).

A horse may need a period of enforced rest should an extraction complication occur so, if competing, surgery is best scheduled out of the competition season.

Importantly, equine athletes that are not showing obvious signs of infection (sub-clinical) may be treated with endodontic techniques to allow the horse to continue competing for a period, with extraction scheduled for the off-season.

How successful is treatment of equine tooth infections?

Equine endodontic treatment has improved over the past 10 years through anatomical studies, improved adaptation of human techniques and availability of better materials.

Infected teeth may need two treatments one month apart to clean the pulp cavity adequately, with long-term success rates of 75% for incisor teeth and 80% for cheek teeth reported.

Most specialists are reluctant to portray such a favourable outlook for cheek teeth RCT, given the lack of procedural sterility, and microscopic guidance to debride adequately and clean the pulp chamber and root canals, as required for human patients. Re-examinations are often needed at three and six months post-operatively and then biannually.

Endodontic treatment is rarely a one-step process as it may be complex, expensive and time consuming. Significant investment in training and equipment will be required by the attending clinician in selecting and completing the appropriate endodontic technique to optimise success. It is important that horse owners are informed fully before treatment begins to help to manage their expectations.

How you can get involved

The author of this article is inviting H&H readers to take part in a short survey to aid his PhD research into this specialist area of equine dentistry. If you’d like to be involved, visit horseandhound.co.uk/endodontic-survey

- For more expert advice on equine veterinary conditions, subscribe to the Horse & Hound website for full access to our veterinary library

You may also be interested in…

An essential guide to equine dental care

Wolf teeth in horses: what you need to know about these tiny, yet troublesome, teeth

Rasping, ageing and helping the long in the tooth: 8 key questions answered about horses’ teeth

14 facts you need to know about your horse’s tongue

Subscribe to Horse & Hound magazine today – and enjoy unlimited website access all year round